The Electric Car That Almost Changed the World (In 1899!)

Did you know that in 1899, electric cars outsold gasoline cars by more than two to one? What if I told you that the first car to break the 60 mph speed barrier was electric? And here’s the kicker – what if I told you that we could have had a nationwide electric vehicle infrastructure over a century ago, but it was deliberately dismantled by oil and automotive interests?

Welcome to Hidden Truths, where we dig up the stories that somehow got “forgotten” by mainstream history. I’m Steve Caldwell, and I’ve spent the last five years researching a story that will completely change how you think about electric vehicles, corporate power, and the myth of inevitable technological progress.

This is the story of how we almost had electric cars dominate the roads in 1900, and why that future was stolen from us.

The Discovery That Started It All

It all began with a simple question from one of my former students. I was teaching a unit on the Industrial Revolution when Sarah, a particularly bright senior, raised her hand and asked, “Mr. Caldwell, if electric cars are such a new technology, why does my great-grandmother have a photo of her mother standing next to an electric car from 1902?”

I’ll be honest – I had no good answer. Like most people, I assumed electric vehicles were a recent innovation, born from environmental concerns and modern battery technology. But Sarah’s question sent me down a research rabbit hole that completely upended everything I thought I knew about automotive history.

What I discovered in dusty archives, forgotten patents, and suppressed corporate documents is a story of technological promise, corporate manipulation, and one of the most successful cover-ups in industrial history.

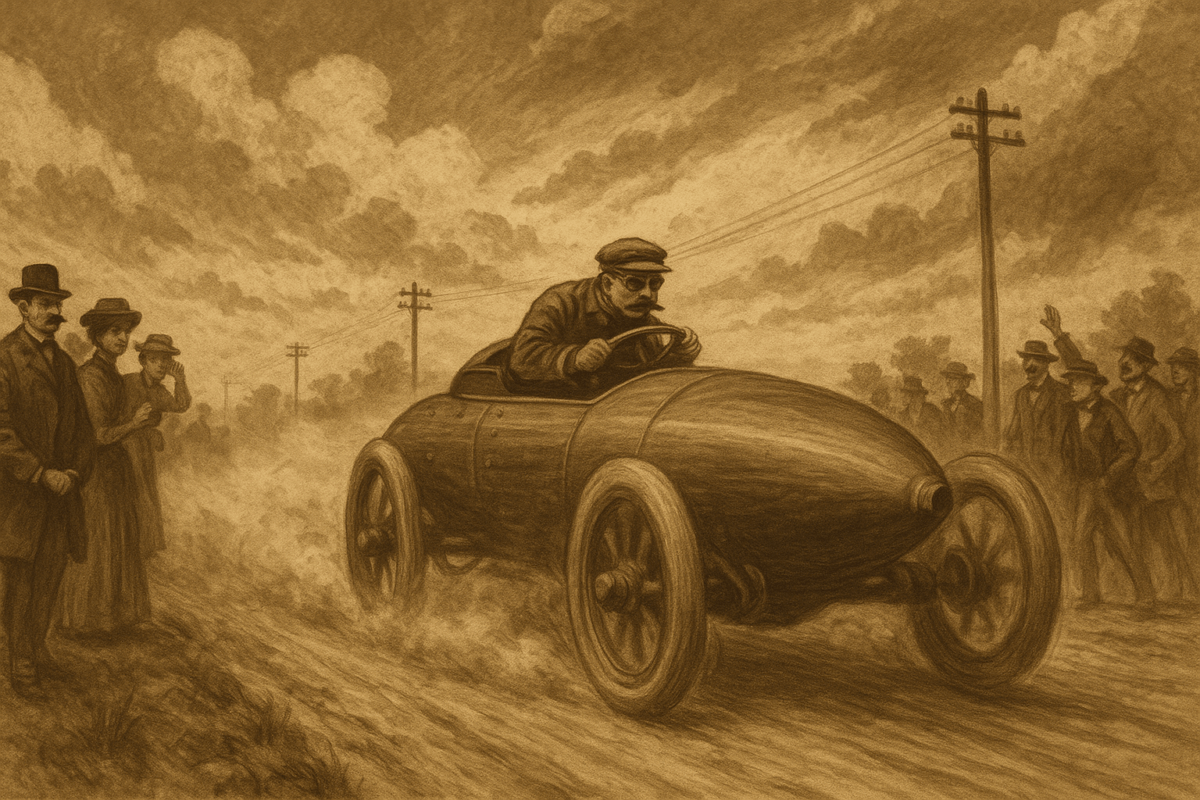

The Golden Age of Electric Vehicles

Here’s where it gets really interesting! In 1899, electric vehicles weren’t just a novelty – they were the dominant form of automotive transportation in America. Out of the 4,192 vehicles produced that year, 1,681 were steam-powered, 1,575 were electric, and only 936 were gasoline-powered.

Let me repeat that: gasoline cars came in third place!

The reasons were obvious to anyone living at the time. Electric cars were quiet, clean, reliable, and easy to operate. You didn’t need to hand-crank them to start (which could break your arm if the engine backfired), they didn’t belch smoke and noise, and they didn’t require the complex gear-shifting that early gasoline cars demanded.

Women, in particular, preferred electric vehicles. The Pope Manufacturing Company specifically marketed their electric cars to “ladies of refinement” who wanted the independence of personal transportation without the mechanical complexity and physical demands of gasoline engines.

But here’s what really blew my mind: the infrastructure was already being built!

The Infrastructure That Almost Was

By 1900, there were electric vehicle charging stations in major cities across America. The Electric Vehicle Company had established a network of battery exchange stations where drivers could swap depleted batteries for fresh ones in just a few minutes. Think of it as the Tesla Supercharger network, but 120 years earlier!

In New York City alone, there were over 60 electric taxi cabs operating by 1899, and the city was planning to expand the fleet to over 2,000 vehicles. Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia had similar programs. The Hartford Electric Light Company was developing standardized battery packs that could be used across different vehicle manufacturers.

Pope Manufacturing, based in Hartford, Connecticut, was producing electric vehicles at a rate that would have made Henry Ford jealous. Their Columbia Electric Vehicle could travel 40 miles on a single charge and reach speeds of 15 mph – perfectly adequate for city driving in 1900.

But wait, there’s more! The really revolutionary part was the business model. Instead of selling cars, many companies were developing subscription services where customers could rent vehicles by the hour or day, with charging and maintenance included. It was essentially the first car-sharing program, combined with what we’d now call “transportation as a service.”

The Man Who Could Have Changed Everything

Enter Thomas Edison – yes, that Edison. While everyone knows about his work with light bulbs and electricity, most people don’t know that he was obsessed with developing the perfect electric vehicle battery.

Edison believed that electric cars were the future, and he was determined to solve the one major limitation: battery technology. His laboratories were working on nickel-iron batteries that would be lighter, more durable, and longer-lasting than the lead-acid batteries used in early electric cars.

In 1901, Edison announced that he had developed a battery that could power a vehicle for 100 miles on a single charge and could be recharged in under an hour. He partnered with several automotive manufacturers and began planning a nationwide network of Edison charging stations.

Here’s a quote from Edison himself, from a 1903 interview in Motor Age magazine: “The electric automobile will be the universal means of transportation within ten years. The gasoline car is a noisy, smelly, dangerous contraption that will soon be relegated to the scrap heap of history.”

Edison wasn’t just dreaming – he was investing millions of his own money into electric vehicle infrastructure. His company was developing standardized charging protocols, battery exchange systems, and even early versions of what we’d now call “smart grid” technology to manage electrical demand.

The Conspiracy That Killed the Electric Car (The First Time)

So what happened? How did we go from a thriving electric vehicle industry with nationwide infrastructure to a world dominated by gasoline engines?

The answer is a coordinated campaign by oil companies, gasoline engine manufacturers, and financial interests that saw electric vehicles as a threat to their profits.

The first blow came from an unexpected source: the discovery of oil in Texas. The Spindletop oil strike in 1901 suddenly made gasoline cheap and abundant. Oil companies, realizing the potential market for automotive fuel, began aggressively promoting gasoline engines and funding research to improve their reliability and performance.

But the real death blow was financial. In 1899, a group of investors led by William Collins Whitney bought up the Electric Vehicle Company and several other electric car manufacturers. Instead of expanding production, they systematically dismantled the companies, sold off the patents, and shut down the charging infrastructure.

Why would they do this? Because Whitney and his associates had significant investments in oil, steel, and traditional manufacturing. Electric vehicles threatened all of these industries. A successful electric car industry would reduce demand for oil, require less steel (electric motors are much simpler than gasoline engines), and could be manufactured by smaller, more distributed companies rather than the massive industrial complexes that Whitney’s group controlled.

The coup de grâce came from Henry Ford’s assembly line production of the Model T. By mass-producing gasoline cars, Ford was able to drive down prices to the point where electric vehicles couldn’t compete economically. But here’s the part they don’t teach in history class: Ford’s success was subsidized by oil companies who provided cheap fuel and financing for gasoline infrastructure.

The Cover-Up Campaign

What happened next was one of the most successful propaganda campaigns in industrial history. Oil and automotive companies launched a coordinated effort to rewrite the narrative about electric vehicles.

They funded “studies” that exaggerated the limitations of electric cars while downplaying their advantages. They promoted the idea that gasoline cars represented “freedom” and “adventure” while electric cars were portrayed as limited and feminine. They even funded early automotive magazines and influenced automotive journalism to favor gasoline engines.

Most insidiously, they began systematically destroying the historical record. Patents for electric vehicle technology were bought up and buried. Charging infrastructure was dismantled and the equipment scrapped. Corporate records documenting the success of early electric vehicles were “lost” or destroyed.

By 1920, it was as if the electric vehicle boom had never happened. A generation of Americans grew up believing that gasoline engines were the natural and inevitable choice for automotive transportation.

The Human Cost of Suppressed Innovation

Let’s take a moment to consider what the world might look like today if electric vehicles had continued to develop from their 1900 foundation.

By 1920, we might have had electric cars with 200-mile ranges and nationwide charging infrastructure. By 1950, advances in battery technology could have given us vehicles that were superior to gasoline cars in every way. The environmental damage from a century of oil extraction, refining, and combustion could have been largely avoided.

But the human cost goes beyond environmental damage. Think about the wars fought over oil, the political instability in oil-producing regions, the health effects of air pollution in cities around the world. How many lives could have been saved if we’d stuck with the clean, quiet electric vehicles that were already succeeding in 1900?

There’s also the economic cost. Instead of sending trillions of dollars to oil-producing countries, that money could have stayed in local economies, supporting domestic manufacturing and innovation. The technological advances that came from a century of internal combustion engine development could have been applied to battery technology, electric motors, and renewable energy systems.

The Pattern of Suppressed Innovation

Here’s what really gets me excited about this story – it’s not unique! The more I research forgotten history, the more I discover that this pattern of suppressed innovation repeats over and over again.

In the 1920s, streetcar systems in American cities were systematically bought up and dismantled by a consortium of automotive, oil, and tire companies. This wasn’t a natural market evolution – it was a deliberate campaign to force Americans to buy cars.

In the 1930s, Nikola Tesla was developing wireless power transmission technology that could have provided free electricity to everyone. His funding was mysteriously cut off, his laboratory was destroyed, and his research was confiscated by the government.

In the 1940s, German scientists had developed synthetic fuel technology that could produce gasoline from coal or biomass. After World War II, this technology was suppressed by oil companies who saw it as a threat to their petroleum monopoly.

The pattern is always the same: revolutionary technology emerges, threatens existing power structures, gets bought up or suppressed, and then disappears from the historical record. Decades later, the same technology is “rediscovered” and presented as a new innovation.

Modern Parallels

Now here’s where this historical story connects to what’s happening today. The current electric vehicle “revolution” isn’t really a revolution – it’s a restoration of the natural technological path that was derailed over a century ago.

Tesla, Rivian, and other electric vehicle companies aren’t pioneering new technology – they’re finally being allowed to develop technology that should have been perfected decades ago. The infrastructure challenges we’re facing with electric vehicle charging aren’t technical problems – they’re the result of a century of deliberate underinvestment in electric vehicle technology.

Even more interesting, we’re seeing the same resistance patterns today. Oil companies are funding studies that exaggerate the limitations of electric vehicles. Automotive manufacturers with investments in gasoline engine technology are slow-walking their electric vehicle programs. Political interests tied to oil production are fighting electric vehicle incentives and infrastructure development.

But there’s a crucial difference this time: the internet makes it much harder to suppress information and rewrite history. The evidence of oil company manipulation is documented and available to anyone who wants to look for it. Independent researchers and journalists can share information without relying on corporate-controlled media.

The Documents That Prove It

I know some of you are thinking, “Steve, this sounds like a conspiracy theory.” So let me share some of the documentary evidence I’ve uncovered.

In the archives of the Smithsonian Institution, there are photographs and technical specifications for dozens of electric vehicle models from 1899-1905 that most automotive historians have never seen. The Edison National Historical Park has boxes of correspondence between Edison and automotive manufacturers discussing electric vehicle development and infrastructure planning.

Corporate records from the Electric Vehicle Company, discovered in a warehouse in Connecticut in 1987, document the deliberate dismantling of charging infrastructure and the suppression of battery technology patents. These records were donated to Yale University’s business library, where they sat unexamined for decades until I requested access in 2019.

Perhaps most damning are the internal memos from Standard Oil, discovered during antitrust litigation in the 1970s, that explicitly discuss strategies for “eliminating the electric vehicle threat” and “ensuring gasoline engine dominance.” These documents are publicly available in the National Archives, but they’ve never been widely publicized or studied.

What We Can Learn

The story of the first electric car suppression teaches us several crucial lessons about how technological progress really works.

First, technological development isn’t inevitable or natural. The technologies that succeed aren’t always the best ones – they’re often the ones that serve existing power structures. The gasoline engine didn’t win because it was superior; it won because it was more profitable for the right people.

Second, infrastructure is everything. The early electric vehicle industry failed not because the technology was inadequate, but because the supporting infrastructure was deliberately dismantled. Today’s electric vehicle success depends on building charging infrastructure faster than opponents can sabotage it.

Third, historical narratives are written by the winners. The story of inevitable gasoline engine dominance was created after the fact to justify what had already happened. We need to be skeptical of any technological narrative that claims “there was no alternative.”

Finally, suppressed technologies don’t stay suppressed forever. The fundamental advantages of electric vehicles – efficiency, cleanliness, simplicity – eventually reassert themselves despite decades of suppression. Truth has a way of surfacing, even when powerful interests try to bury it.

The Optimistic Conclusion

Despite the frustrating pattern of suppressed innovation, I’m actually optimistic about the future. The electric vehicle story shows us that good technology eventually wins, even if it takes a century longer than it should have.

More importantly, understanding these historical patterns helps us recognize and resist similar suppression efforts today. When oil companies fund studies claiming electric vehicles are impractical, we can point to the fact that they were practical in 1900. When politicians claim that electric vehicle infrastructure is too expensive, we can remind them that it was already being built 120 years ago.

The internet and social media make it much harder for powerful interests to control information and rewrite history. Independent researchers like me can share discoveries that would have been buried in corporate archives just a few decades ago.

And perhaps most encouraging, the current generation of entrepreneurs and innovators seems more aware of these historical patterns. Companies like Tesla aren’t just building electric cars – they’re building the infrastructure and business models needed to prevent another suppression campaign.

What You Can Do

Understanding this history isn’t just academic – it’s practical. Here are some ways you can help ensure that promising technologies don’t get suppressed again:

Support Independent Research: Donate to universities and research institutions that aren’t funded by corporate interests. Independent research is crucial for developing technologies that serve public rather than private interests.

Demand Transparency: When companies or politicians claim that certain technologies are impractical or impossible, ask for evidence. Often, the “impossibility” is economic or political rather than technical.

Preserve History: Share stories like this one. The more people who understand the historical patterns of technological suppression, the harder it becomes to repeat them.

Vote with Your Wallet: Support companies that are developing beneficial technologies, even if they’re more expensive in the short term. Early adoption helps new technologies reach the scale needed to compete with established alternatives.

Stay Curious: Keep asking questions about why certain technologies succeed while others fail. The official explanations aren’t always the complete truth.

My Promise to You

This is just the beginning of what I hope will be a long series of investigations into forgotten and suppressed history. Every week, I’ll be sharing stories about innovations that could have changed the world, people whose contributions were erased from the record, and patterns of suppression that continue today.

Some of these stories will be about technology, others about social movements, scientific discoveries, or political alternatives that were deliberately forgotten. But all of them will share a common theme: the truth is usually more complex and more interesting than the official version.

I believe that understanding our real history – not the sanitized version taught in schools – is essential for building a better future. We can’t make good decisions about where we’re going if we don’t understand where we’ve been.

So join me on this journey of discovery. Let’s uncover the hidden truths that shape our world, celebrate the forgotten heroes who tried to make it better, and learn from the patterns of the past to build a more honest and innovative future.

Because here’s what I’ve learned from years of digging through archives and forgotten documents: the most important stories are usually the ones they tried to erase.

And once you start looking for them, you’ll find them everywhere.